Today is the last day of Banned Books Week, and I intentionally left Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials for my final selection. That is because a lot of things begin and end and begin again with the series. It’s a story as grand and sweeping as John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), laden with history, poetic intent, theological agitation, and a thirst to reframe the grand narratives that have dictated our lives for centuries. When Pullman references Blake, Milton and parables from the Bible, he situates the reader within an ongoing conversation about faith and the nature of sin. Although the worlds that Lyra and Will explore have some real-world equivalents, Pullman is a master of world building. He crafts the universes so deftly and intricately, with such meticulous attention and believability, you can only truly appreciate the invention when you take a step back and allow the masterpiece to sink in. Like his literary precedents, Pullman wants to create a narrative with mythic, moral dimensions, motivated by grandiose, existential themes to unravel a new story about the universe, one as important and meaningful as other religious texts. He manages to achieve these goals with grace and dexterity.

His Dark Materials came to me just as I was undergoing my first in-depth study of the Bible. As a part of my Episcopalian upbringing, I had to undergo Confirmation classes before I reaffirmed my faith in Christ. I expected that this class would expose me to the other religious doctrines of the world, like Islam, Buddhism, Hindu, so that I could make an informed decision about my faith. I had already begun to question the principles upon which my parents’ religion was founded and had difficulty with the concept of faith without proof. As I began to read the Bible more thoroughly, the internal contradictions, hypocrisy and sexism became more and more evident. I became enraged when my pastor told me that I had been made from the rib of Adam and was born in original sin due to the fault of Eve. There were a multitude of other misgivings and questions that began to furrow my faith, especially as I became less and less convinced of the veracity of the stories and more and more assured that religion is a story we use to organize and make sense of the world. When I first picked up The Golden Compass (1995), all of these questions were swirling around my head, and while I was initially captivated by the magical landscape of Lyra’s imagination—the trepanned skulls, the reanimated bodies in the crypts of Jordan College, the stories of child abduction—the book also commenced to set Lyra’s adventure in motion with the question of Dust. The rumors of kidnapping by the Oblation Board were also circulating around real-world South Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe as well, products of the black market organ trade, but Pullman uses the urban legends as an entre to discuss the horrors of the Catholic Church and introduce the pernicious character of Mrs. Coulter, Lyra’s mother. Science, speculation and faith converge around questions of innocence in children and the lengths to which the Church will go to cement their power in an age of premature technological advancement, when the world seems on the verge of change.

Lyra is a flawed, quick-tempered, imaginative child, and will always be one of my favorite female characters ever written. She is fiercely loyal, easily draws friends around her, and devilishly precocious. The Golden Compass is built around Lyra’s quest to save Roger from the Oblation Board, with the help of Serafina Pekkala and her witches, John Faa and the Gyptians, and Iorek Byrnison, an armored bear of the north. She discovers the hideous experiments conducted by her mother and the Church to sever the connection between child and daemon in the name of scientific inquiry and theological speculation. The connection between daemon and child is seen as sacred, and perhaps the most fascinating element of the narrative in the relationship between Lyra and Pantalaimon as they grow and mature, two halves of the same whole. Lyra discovers that her quest to discover the nature of Dust is shared with her father, Lord Asriel, who forms a bridge across worlds and hopes to lead a rebellion against the Church. Thus does Lyra transcend the permeable boundaries between worlds and search for answers amidst the panoply of universes, aided by her Alethiometer or truth finder.

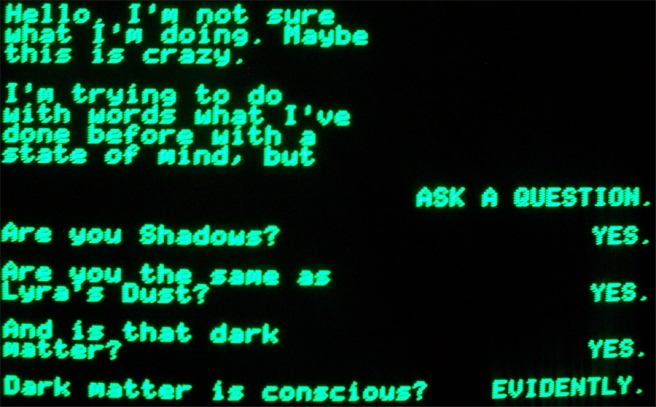

Throughout the next two books, The Subtle Knife (1997) and The Amber Spyglass (2000), the scale of the quest for answers expands greatly. Lyra encounters and teams up with Will Parry, a boy from contemporary London whose father disappeared inexplicably on an expedition North. Though intelligent, street-smart children, they find themselves outwitted by adults and attacked by the kids of Cittàgazze, a world that seems to intersect at Lyra and Will’s present. Will is entrusted with the Subtle Knife, a weapon that can slice windows between worlds, and Lyra befriends physicist Dr. Mary Malone. Malone and Lyra negotiate the differences between dark matter and angels, two theoretical principles that reference the same force of energy and, it turns out, consciousness. As I read Mary Malone’s conversation with angels in my middle school library, it felt as though I too had ripped through the fabric of my universe. That is the power of Pullman’s prose—his story seems unequivocally real, so real that the events of The Amber Spyglass have crucial resonances for the reader.

The clash between the forces of Heaven and Lord Asriel’s army coalesce in The Amber Spyglass. While Lord Asriel enlists the fallen heavenly hosts for his revolution, Will and Lyra descend into the world of the dead. The books are full of moments of utter sorrow and grief, and the abandonment of the daemons on Charon’s dock is perhaps one of the most tragic. Through Lyra’s storytelling abilities and empathy, she is able to transform the nature of death into the most beautiful formulation of moving on I have ever read, fictional or otherwise. Previously imprisoned by Harpies, Lyra leads the dead to an impasse where Will cuts a window into the living world. The dead rejoice, saying, “Even if it means oblivion, friends, I’ll welcome it, because it won’t be nothing. We’ll be alive again in a thousand blades of grass, and a million leaves; we’ll be falling in the raindrops and blowing in the fresh breeze; we’ll be glittering in the dew under the stars and the moon out there in the physical world, which is our true home and always was” (Pullman 2000), noting how they will become a part of their daemons and loved ones again. Quite apart from becoming the girl who defeats, or rather improves death, Lyra joins Lord Asriel’s fight against the Authority, the first angel who has used his celestial power to oppress mankind and allow wickedness to spread in the name of justice. As Ruta Skadi, another witch pronounces, “For all of [the Church’s] history… it’s tried to suppress and control every natural impulse. And when it can’t control them, it cuts them out […] That’s what the Church does, and every church is the same: control, destroy, obliterate every good feeling” (Pullman 1997:286). Pullman does not indict the Church for its belief system, but rather the way that its beliefs have been used to justify overt and covert forms of violence against humans, as well as the way that it does not allow for the celebration of alternative belief systems and ways of being in the world.

Mary Malone is one of the most sympathetic characters to the Church. Formerly a nun, she speaks to the sense of comfort and purpose her faith gave her, but also recognizes that you can find similar forms of celestial wonder and existential solace through different professional or spiritual avenues. Forced to escape from the Church for her research on dark matter, Malone travels to the world of the Mulefa, a species of sentient beings with a completely different physiological structure than anything we’ve seen on earth. I think the Mulefa are perhaps among the most important creatures in His Dark Materials. They are not anthropomorphized, as so many alternative, alien species are. Pullman does an excellent job of demonstrating how the creatures evolved in a symbiotic relationship with the environment. While Lyra’s polar ice caps are melting from global warming caused by the bridge across worlds, the Mulefa live in harmony with their ecological system. The Mulefa reconfigure what it means to be conscious or human, with a complex linguistic, cultural system Mary comes to love and respect. The strange looking creatures, that do not even possess the same musculature for speech that humans do, have much to teach Mary, a physicist, highlighting the empathy and intention that must go into interactions across cultures and, potentially, across species.

It is in the world of the Mulefa that Lyra and Will also discover their sexuality. Under the sage advice of Dr. Malone, the couple finally has a chance to explore their love for one another and divest the secrets of one another’s bodies. Rather than a shameful, sinful act, sex is the source of salvation for the universe. The very trees of the Mulefa world are crying out for Dust, need it to maintain the vitality of their world. Sex and love create Dust, a substance that is inherently beneficial to the world. This principle is, perhaps, the most important part of His Dark Materials. Whether or not you find the anti-Christian sentiments abrasive, Pullman eliminates the self-hatred and misogyny endemic of Christianity. As a woman, reading The Amber Spyglass, I felt as though Pullman was absolving my gender of the sins we had historically been laden with and allowing us to celebrate life whole-bodied, eliminating the shame we had been saddled with for centuries. I wouldn’t call His Dark Materials an atheist series, because there is such poignant wonder and enchantment throughout the worlds. I believe that Pullman, rather, is inviting his readers to acknowledge the alternative spiritualities the can foment in a world such as ours, and consider the ways that religious doctrines may hurt more than they help. He is a fierce opponent of corruption and oppression, but his every sentence blossoms with marvel at the natural world, and the beauty of creation. Just as you fall in love with the language of the Devil in Paradise Lost, you learn to see the world anew, from alternative perspectives, through Pullman.

According to the ALA, Pullman’s series was number two on the Top Ten Most Banned Books of 2008. Many of the critics and censors are religious organizations who indict His Dark Materials as anti-Christian, or find fault for his inclusion of witches. But as Pullman writes in The Amber Spyglass, “I came to believe that good and evil are names for what people do, not for what they are. All we can say is that this is a good deed, because it helps someone or that’s an evil one because it hurts them. People are too complicated to have simple labels” (2000) and the author is tirelessly concerned with what it means to do the right thing. Lord Asriel’s efforts to overthrow the Authority are to depose a structure that willfully inflicts pain and tragedy upon people. At the end of the series, Will and Lyra are faced with a choice between their own romantic desires and the needs of universe, the health of the worlds they have flitted in and out of. The sacrifice that they make for the good of the universe is utterly heartbreaking and teaches the same lessons of charity and selflessness many homilies also preach. How can we live our lives so that they leave behind vivid bursts of happiness?

His Dark Materials is one of those series that lingers with you, even after you’ve closed the books. I can honestly say that the books radically shaped my outlook on the world, and remain a lasting influence in my life. It’s one of those series that lives in your bones. I am eternally grateful to Philip Pullman for crafting such an accessible yet magisterial narrative, one that has helped me to become the person I am today.

Works Cited

“Frequently Challenged Books of the 21st Century” (2014). ALA. http://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10#2010

Milton, John (1667). Paradise Lost.

Pullman, Philip (1995). The Golden Compass. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Pullman, Philip (1997). The Subtle Knife. New York: Random House, Inc.

Pullman, Philip (2000). The Amber Spyglass. New York: Random House, Inc.